Over the ocean temperature changes are small, which is why out at sea there is no huge difference in weather conditions between day and night. Meteorologist Chris Tibbs explains what to look out for instead

As a group of islands the UK has a maritime climate to match our maritime history. Being surrounded by the ocean does mean that our weather is significantly influenced by the sea water temperature, giving us mild, but wet winters and warm, but still quite wet summers. This was particularly true this winter as record rainfall and temperatures were experienced.

Our geographical position gives us the influence of the tropical warm water that comes first through the Straits of Florida as the Gulf Stream running up the east coast of the US as a river of warm water before turning east as it continues across the Atlantic as the North Atlantic Drift. It reaches our shores to give us a warmer sea temperature than we would normally expect for our latitude.

It always surprises me when looking at a map that London is on a similar latitude to Labrador, Glasgow the same as Moscow and Lerwick south Greenland, however our weather is much more moderate than these places because of the Gulf Stream and the warm water lapping our shores.

The reason why the water temperature moderates our air temperatures is fundamental to all of meteorology. We know that the air is mostly transparent to the incoming short-wave radiation from the sun, but the land and sea are not, so they warm up.

Photo: Paul Wyeth

The land quickly warms in the sunshine, heating the air above. Then during the night the land radiates long-wave radiation and quickly cools, giving a large diurnal change in the temperature.

However, over the sea the water temperature only slowly increases in the sun’s radiation and, although the sea will radiate at night, the daily change in water temperature between day and night is very small.

Small temp change at night

When sailing offshore there is only a small temperature change – around the UK we may add a jumper at night, but the temperature difference is minimal. If we look at buoy reports, the difference in air temperature does not change very much between day and night whereas on land there will be a large difference.

The large daily change in temperature over the land gives us the ‘normal’ coastal wind pattern of light wind overnight as the land cools and the air above it also cools, sinking to the ground where the air is slowed by friction.

During the day the heating land will add energy to the atmosphere, allowing the wind to increase and quite possibly a sea breeze to develop.

At sea the difference in air temperature does not change very much between day and night whereas on land there will be a large difference.

If we measure wind speed against time we find that on average the maximum wind speed will be at the time of maximum temperature, which is mid-afternoon.

Out at sea, however, this is unlikely to be the case as the change in temperature through the day is minimal so we look to other influences to explain the changes in wind speeds. If we remove large scale synoptic features, what will cause the wind speed to change throughout the day?

Cloud cover is one thing, we know that cloud top temperatures will drop at night as the clouds radiate energy to space. One theory goes that, as the clouds cool, the contrast between the sea surface temperature and the clouds increases, causing more turbulence and instability, which in turn increases the wind speed.

This would also tend to explain an increase in the frequency of squalls at night and early morning in the tropics where there is a diurnal pressure change that will also alter wind speed by a few knots.

Passagemaking/racing tips

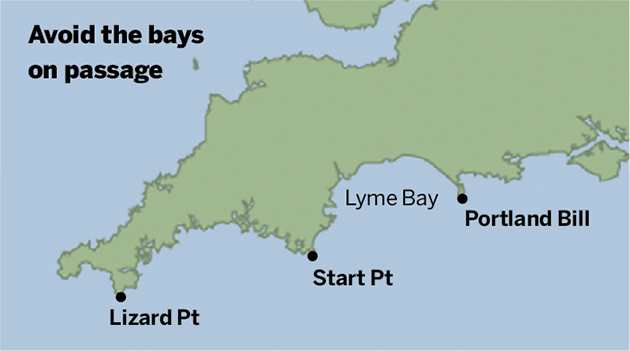

- Avoid getting close to the coast at night particularly into bays where the wind is likely to be considerably lighter.

- The coldest part of the night is near dawn, which will give the lightest coastal wind.

- Try to approach the coast at night from offshore rather than closing the coast and following it to your destination.

- The opposite can be said for the daytime when wind is likely to be strongest along the coast although bays are still likely to give lighter wind so are best avoided.

- The transition between the synoptic wind and a sea breeze creates a band of light wind and it is sometimes better to stay well offshore than to try to catch a temporary sea breeze further inshore.

Chris Tibbs is a meteorologist and weather router, as well as a professional sailor and navigator, forecasting for Olympic teams and the ARC rally. He is currently on his own circumnavigation with his wife, Helen. His series of Weather Briefings can be seen here

See also:

Chris Tibbs prepares his own boat for an Atlantic crossing

The best route for an Atlantic crossing

Taking the northerly route across the Atlantic

Offshore weather planning: options for receiving weather data at sea

as well as Chris Tibbs’s series of Weather Briefings